What is MCAS?

Mast cells are an important part of your immune system and help fight infection. They’re found throughout your body, particularly in your bone marrow, which is where they are produced, and around blood vessels.

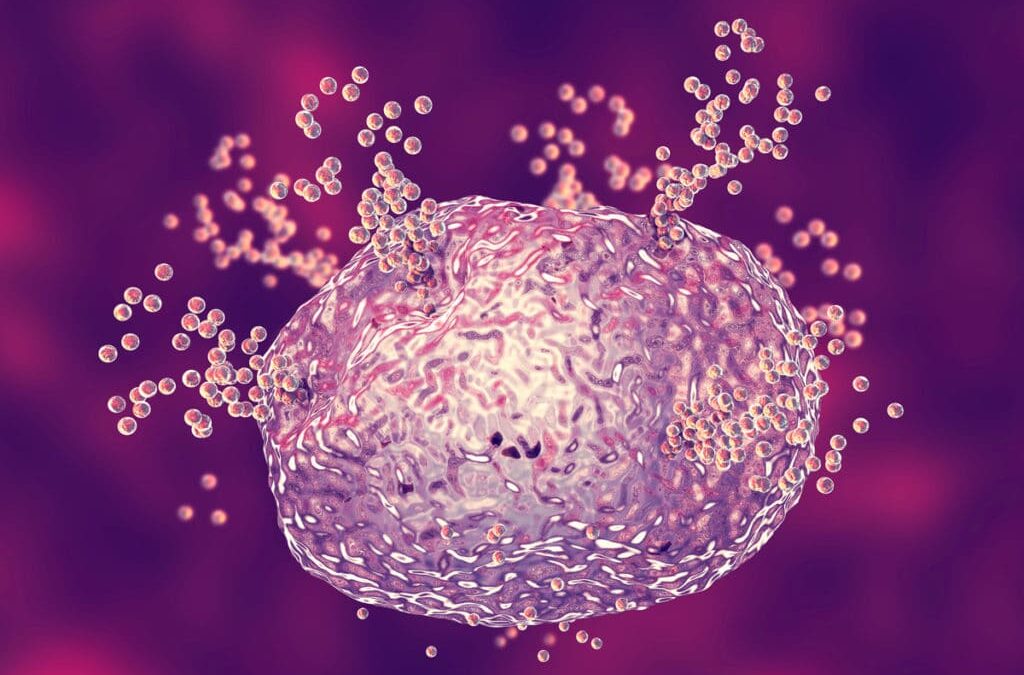

Typically, mast cells will release chemical mediators into the bloodstream, one of which is histamine, in response to exposure to allergens, including certain medications, foods, and insect venoms. The most well-known mediator is histamine, but they also include tryptase, prostaglandins and leukotrienes.

In a healthy person, the chemical mediators help protect and heal. However, in someone with MCAS, they have a negative effect. In cases of MCAS, your mast cells release these same mediators too frequently and too often on their own (without exposure to an allergen)

Mastocytosis, a variant of primary MCAS, happens when your body produces too many mast cells in one or more organs within your body. These cells can continue growing and tends to be overly sensitive to activation and mediator release. More mast cells mean more chemical mediators are released, causing an allergic-like reaction and sometimes anaphylaxis.

These symptoms can interfere with your daily life. While the exact causes of MCAS are still unclear, proper diagnosis and treatment can help you manage your symptoms

Symptoms

The number of mediators released can cause symptoms that range from mild to life threatening.

The symptoms of MCAS range from severe itching and swellings to full-blown allergic reactions (anaphylaxis), which may be life threatening. Patients with MCAS can either develop symptoms spontaneously or after exposure to substances to which they are allergic (for example wasp stings)

Symptoms can start at any age, but usually begin in adulthood. Every part of the body can be affected by these symptoms. These symptoms may include:

• Itching of the skin

• Hives

• Sweating

• Eye watering

• Itching and running of the nose

• Itching and/or swelling of the tongue or lips

• Swelling of the throat

• Trouble breathing, wheezing

• A low bp

• Rapid heart rate

• Stomach cramps

• Nausea

• Diarrhoea

• Abdominal pain

• Headaches

• Feelings of confusion

• Fatigue

In severe cases, you may experience anaphylactic shock, which requires emergency treatment. The symptoms of anaphylactic shock are as follows: a rapid drop in blood pressure, light-headedness, weak pulse, trouble breathing or quick and shallow breathing, confusion, and loss of consciousness.

Triggers

Researchers aren’t sure what causes some people to experience MCAS. Some studies do suggest there may be a genetic component to MCAS. There are three types of MCAS:

Primary MCAS occurs due to a certain genetic mutation, and the mast cells display CD25, a certain protein. Primary MCAS often occurs with a confirmed case of mastocytosis (when the body produces too many mast cells) If you have primary or idiopathic MCAS, symptoms will occur without exposure to any particular trigger.

Secondary MCAS occurs as an indirect result of an underlying trigger, for example another immunological condition, a food/ environmental allergy, or hypersensitivity to another trigger. With secondary MCAS, you will likely find that exposure to certain things can trigger your symptoms. Some triggers can be things like infections, medications, insect or reptile venom, fragrances, stress, exercise, certain foods, alcohol, infection, wasp/ bee stings, and insect bites.

Idiopathic MCAS is when the cause cannot be determined. Most cases are idiopathic. MCAS has also been associated with obesity, IBS, depression, and diabetes. We don’t yet know if MCAS plays a role in the development of these conditions, or if it’s the other way around, but we do know they’re connected.

Can you test for MCAS?

An American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology work group report proposed the following criteria for diagnosing MCAS:

->You have recurrent, severe symptoms (often anaphylaxis) that affect at least two organs. ->Taking medications that block the effects or release of mast cell mediators reduces or resolves your symptoms. Mast cell mediators can include: tryptase, histamine, prostaglandin (PG) D2, leukotriene (LT)

->Blood or urine tests taken during an episode show higher levels of markers for mediators or their metabolites than when you aren’t having an episode.

Diagnosis is based on the symptoms, clinical exam, and specific laboratory testing.

Other conditions may need to be excluded before MCAS can be diagnosed.

MCAS itself can be difficult to diagnose as test results can often be normal unless there are significant symptoms present at the time of doing the test. Another problem is the symptoms are rather non-specific.

This is made even more complicated by the fact that there’s no single test used for point 2). Serum tryptase and whole-blood histamine can be used as markers, but so can urinary histamine metabolites such as N-methylhistamine.

Managing MCAS

While there is no cure for MCAS, there are ways to manage the symptoms.

Management is based on the avoidance of triggers, and medication to help to control symptoms.

Antihistamines block off the effects of histamine, which is one of the primary chemical mediators that the mast cells release. This can help with symptoms such as itching, stomach pain and nausea.

Antileukotriene medications block the effects of leukotrienes, another common type of mediator, to treat wheezing and stomach cramps.

Aspirin may also decrease flushing if that is one of your symptoms.

If a doctor diagnoses you with secondary MCAS, you may find that certain foods trigger your symptoms. You should discuss changes to your diet with a doctor and avoid foods that trigger a reaction.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that low histamine diets may help some people manage symptoms of MCAS, though scientific research doesn’t currently support this. A low histamine diets limits foods generally thought to be high in the chemical histamine, which mast cells release when they’re activated. Foods that are high in histamine can include hard cheese, fish, spinach, sausage, and alcohol.

For some, this can bring great symptomatic relief. But it doesn’t work for everybody. This is because a low-histamine diet

a) doesn’t entirely influence how much histamine your body makes

b) doesn’t control how your body breaks down histamine and

c) doesn’t tackle the other mediators that could be causing MCAS problems: tryptase, prostaglandins and leukotrienes.

Corticotropin hormone, released when you’re under stress, destabilises mast cells. This means a stress-reduction practice is an essential part of tackling MCAS.